Interviews with notable steel guitar players. Paul Franklin, Pete Drake, Herb Remington and Rusty Young.

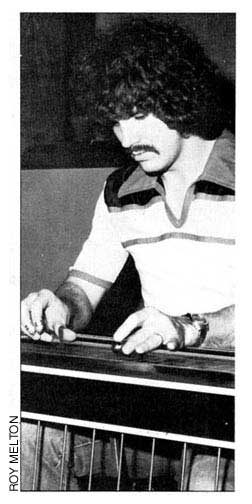

Paul Franklin

by Cal Sharp

Guitar Player Magazine October, 1980

PAUL FRANKLIN is one of the newer breed of steel guitarists who is changing the whole concept of the instrument.

Noted for his supple single-string picking style and use of numerous effects - including a Korg X-911 guitar synthesizer - he elevates the steel guitar beyond its traditional role, infusing it with a meaning of its own apart from country and Hawaiian music. When Paul's not on the road as a member of country singer Mel Tillis' band, he jams around Nashville, does recording sessions with the likes of Linda Hargrove and Jerry Reed, answers calls for commercial jingles for RC Cola, Chevrolet, and others, cuts his own LPs, tapes steel guitar instructional material, and helps his father build Franklin steel guitars

Paul Franklin was born on May 31, 1954, in Detroit, and there was always a great deal of country music around the house since his father, Paul Sr., loved the steel guitar. When the younger Franklin was eight, his father asked him if he would like to play an instrument, and the son replied a steel was what he desired. So Paul Sr., an inveterate tinkerer, converted an old Vega guitar into a dobro-like instrument. Paul plucked on this for about six months, after which he got his first pedal steel, a Fender 400.

Except for a Hawaiian steel guitar teacher who knew nothing about pedals, but who was able to show Paul the rudiments of picking and bar control, there were virtually no professional steel players or instructors around Detroit. So Franklin learned licks as best he could by listening to records by steelers such as Buddy Emmons, Jimmy Day, Hal Rugg, Pete Drake, and Curley Chalker. His dad helped him a lot in these formative years, never demanding but always encouraging him to learn solos exactly as they were played on the records. Paul Sr. would also take his son to clubs, jamborees, and shows where he could hear - and sometimes play - exposing him to hot road musicians such as Buddy Charleton, Sonny Garrish, and Jimmy Crawford.

By the time Paul was 11, he decided that all he wanted to do was to play steel guitar. He worked clubs and sessions around Detroit (he played on the Gallery LP, It's So Nice To Be With You [out of print], when he was 16), and by the time Paul was 17 he grew tired of his hometown scene and moved to Nashville.

Country music players, disc jockeys, and fans have a big celebration every year in Nashville called the DJ Convention where jam sessions are an important part of the proceedings, and Paul's father had been taking him to them since his early teens. Everyone was amazed to see this youngster holding his own in jams with seasoned pros, and the reputation Franklin built there led to his first Nashville road gig at 17 with Barbara Mandrell. Since then he's performed with Lynn Anderson, Donna Fargo, Jerry Reed, and, most recently, Mel Tillis.

Franklin has also spent a great deal of time in the Nashville studios, recording with Linda Hargrove (Love, You're The Teacher, (Capitol, ST 11463) andImpressions, [Capitol, ST 11685], Brewer & Shipley (One Toke Over Tire Line,[out of print], Jerry Reed (Half And Half, [RCA, AHL I-3359]), and Mel Tillis (Mr.Entertainer, [MCA, 3167] and Your Body Is An Outlaw, [Elektra, 6E271]), to name a few. Franklin has also recorded two solo LPs: Just Pickin ; a mixture o fE9th country and C6th bebop, and Play By Play, a jazz-rock collection (both are available from Scotty's Music, 9535 Midland, Overland, MO 63114).

Concerning studio work, Paul has mixed feelings. He enjoys the challenge, especially when it gets him into more reading and opportunities for creative playing. But too many times, he feels, a producer will hire musicians because they're hot at the moment, rather than because their playing style best suits the material to be recorded. While Paul says that the steel guitar is becoming more accepted by non-country players and listeners, he admits that it still has a long way to go.

"So many people have already stereotyped the steel guitar," he says. "'I have a set way of thinking how it should sound and the way it can lit into a song. While I'm not against the way anybody's approaching the instrument, some producers seem to want you to come in and play like someone else. If you rebel against this and say, 'Hey, l want to try something different,' they often try to place you in a position where you feel you're putting down the other guys. `What? Isn't this good enough for you?' they ask. And some of the older steel guitarists will even say, `Why don't you play this?"They're resisting change, I guess, and this attitude has sometimes been a problem for me. But now that I've been accepted in Nashville after eight years of working in the studio there, I can pretty well go in and play myself. But it was a battle for a long time, and it's still a problem on occasion. That, however, is part of the thrill and challenge of playing: trying to convince people that something can be done differently."

Franklin is on the road quite a bit as a member of the Statesiders, Mel Tillis' band. Mel carries guitar, steel, piano, bass, drums, and three fiddles, and there are approximately 13 people who tour with him, some using a bus while others travel on a six-scat airplane. While the band plays big showrooms almost exclusively, renting PA equipment as they go, they've also done quite a few TV shows lately. Paul plays mostly straight 0th country licks with Mel, but the Statesiders do get a chance to turn loose every once in a while, and it's then that Paul flexes his C6th chops.

When Franklin first moved to Nashville he roomed with a bassist named Randy Hillman. Randy was heavily into jazz, and when Paul began listening to his record collection, it opened up many new musical vistas. Franklin never had much formal musical training, but his Hawaiian teacher in Detroit had taught him to read, and he put this knowledge to work as he began to explore scales, modes, and other elements of music theory. Until recently Paul wasn't fanatical about practicing; an hour or so a day seemed sufficient to enable him to keep up with what was being played on most hit country records. But as he became more interested in jazz and pop music he began to spend more time woodshedding to build his chops.

Often Paul will listen to records at home and imagine his steel is a sax, or even a synthesizer, playing lines that he thinks those particular instruments might do. He finds synthesizer lines to be especially adaptable to the steel guitar due to the steel's virtually unlimited capacity for bends and glisses.

Study aids Franklin finds particularly useful for musicians are those published by Jamey Aebersold, and he is currently studying George Russell's Lydian Chromatic Concept. Another part of the learning process is listening, and Paul absorbs a lot of music, trying to understand the basic concept behind each style. "Actually, I don't listen to steel guitarists at all now," he says. "My earlier influences were Buddy Emmons, Doug Jernigan, people like that, but presently I'm trying to approach the instrument from a jazz and fusion context, so I'm getting into a lot of [keyboardists] Chick Corea and Herbie Hancock. My goal on the instrument is to take it into a place where it hasn't been accepted yet. Like, I would love to play with Steely Dan if they were ever to want a steel guitarist. And to be prepared for that, you have to study from where those musicians are drawing their music. I don't think Steely Dan's listening to Buddy Emmons or other steelers: They're into Cannonball Adderly and whatever, and then applying it to their music. That's what I'm doing with my pedal steel, too.

"Something that has held the steel guitar back is the fact that people have a set tone they listen for. If it doesn't sound like what has been traditionally done, then they say, `Well, that's bad tone.' But I'm trying to be more open-minded; I don't want to have merely a straight E9th country sound. I think every steel player should learn how to get that tone, but I don't put as much importance on it as I do on the way the guy's thinking and improvising. For instance, a lot of traditionalists would probably say Sneaky Pete Kleinow's tone on Stevie Wonder's albums was bad, but to me that's great tone because it didn't sound like a steel. I think that what makes the instrument different, instead of its tone, is the way it's played."

Franklin's picking style emphasizes single-string runs based on scales and modes, rather than employing numerous chord fills. "I know all the chords you can make on a steel because I went through that," he says. "But I play the guitar like a saxophonist or a keyboardist would their respective instruments. When it comes time for soloing, I stress the single-note improvisation instead of the old-school approach where you play chords like a whole horn-section ride. Since you don't

have every inversion of all the chords on a steel, it's really a limited instrument when you approach it that way. But single-note-wise, if you set your pedals up for all the scales, you can do anything that you could on a keyboard, basically. You have to get the knowledge yourself, but it's all there in the tuning."

With the unusual fingering technique which he employs, Franklin has broadened many steel guitarists' conceptions of what the instrument is capable of achieving. Instead of blocking with the back of his hand as most players do, he rests his hand on the strings with his picks dug into them, ready for action. With an upward motion of the fingers he contacts the strings and then puts his fingers back down on them to block. With more conventional techniques, the hand is held above the strings. When one is to be picked, the finger moves down, strikes the string, moves back up, and then either the back of the hand or the pick itself blocks.

Paul plays a Franklin [712 May Dr., Madison, TN 37115] double-neck steel guitar. His father, who was employed at Sho-Bud for several years doing custom work, started building his own guitars two years ago. One interesting characteristic of the Franklin steel is its ability to raise or lower a string one entire octave, thus making any kind of pedal feel-from soft to hard, or long to short - available to the player. On many other guitars, Paul found that while playing, say, thirty-second notes at certain tempos, the pedals wouldn't return quickly enough to get the next note out. This is not a problem on the Franklin guitar. "It's faster than I am;" Paul says.

Another interesting feature of the Franklin is its innovative tuning mechanism, which uses nylon compensators to keep the strings in tune after working the pedals. Paul explains: "There's been an age-old tuning problem with the steel guitar. On almost all brands, when you raise a string and then release it, it stays in tune; but when you lower that same string, it will come back sharp. My father devised these nylon tuning compensators, however, to eliminate that problem. You can fine-tune each string individually with his system." In addition, the Franklin steel has two output jacks, thus allowing the user to play in stereo. "That's one of the things I've always liked about it," he says. "Because most studio situations nowadays find the guitarist doubling himself, the Franklin lets you do it live - it sounds like two steels playing at once, especially if you have one straight signal and the other run through effects."

Paul also uses a number of effects when he performs, including a ProCo Rat Fuzz, a Roland Boss Chorus Ensemble, an ElectroHarmonix Memory Man echo unit, and a Korg X-91 I guitar synthesizer. His amplifier is a Peavey Session 400 with a 15" Black Widow speaker, and while playing he sets the presence on three, the treble on seven to eight, the reverb on six to eight, and the bass on zero. Paul's lack of any bass may seem odd at first, but because he wears his National fingerpicks jammed tightly on his fingers and-as he explains it-picks with the meat of the pick instead of the tip, it creates a fuller sound when striking the strings (in Paul's case, Bill Lawrences), making extra bass on the amp unnecessary.

Franklin prefers using a doubleneck guitar instead of trying to combine theE9th and C6th into a single-neck universal tuning. Because he works mainly from scales, he feels that it's important to utilize the same scale positions and patterns ond the top strings as on the bottom, and he likes to play any given scale or pattern all the way across the guitar, from the first string to the last.

Paul's E9th tuning is fairly standard, but his C6th neck has a few unique features (see copedent). For example, his fifth pedal makes quite a dramatic change in the tuning: By using it in conjunction with the sixth pedal and the RL (right knee moving left) lever, he can play all the modes within three frets. Chromatic notes, too, have always been difficult to play quickly and cleanly on the C6th neck; Paul's LL (left knee moving left) lever solves this problem.

At 26 years old, Paul Franklin's ultimate goal is to get beyond scales, modes, chords, and rehearsed patterns and to play with feeling more than with a conscious regard for the technicalities involved - "to let the instrument play itself," as he says. "With any instrument, if you're closed-minded about it, you're only going to play limited. That's what has happened with the pedal steel guitar. I feel that there is yet to come along someone open-minded enough to play it the way it can be played. The real innovators have been guys like Emmons, Jernigan, Sneaky Pete, and Sonny Garrish. Emmons was always sort of rebellious; he never got into the fast chord-playing thing so many others did. He just went single-note and kept with it. Recording-wise, I think Sonny Garrish is doing more for changing the way the pedal steel sounds on records out of Nashville than anyone. A lot of his stuff you don't hear because it's jingles and hooks, but he's playing it more like a keyboard than a pedal steel. And Doug Jernigan with his single-note things; he's also one of the innovators. "But you have to be open-minded to innovate. If you're what I call a rounded musician - a full-circle musician, you dig a little bit of everything: McLaughlin, Carlton, Martino, Di Meola, or whomever. Then you can play a little bit of everything, and you can adapt to any situation. I think that's being a musician. I'm striving to be a musician, not a pedal steel guitar player."

Pete Drake: everyone's favorite

by Douglas Green

Guitar Player Magazine

Nashville pedal steel guitarist Pete Drake is truly a phenomenon. Not only has he been the man behind hundreds of country music hits, but through his recordings with Elvis Presley, George Harrison and Bob Dylan, is singlehandedly responsible for opening the entire pop and rock field to the sounds of the pedal steel.

Pete was born in Georgia forty years ago, but it wasn't until he was eighteen that he began playing steel guitar. Like so many before and since, Drake was inspired by the sounds of Jerry Byrd at the Grand Ole Opry. Pete then spotted a lap steel guitar in an Atlanta pawn shop, saved his money and bought it for the vast sum of $38.00.

What kind was it?

A Supro; a little, single-neck like you hold in your lap. I tried to play like Jerry Byrd. I guess most of the steel players today started off the same way. He has really been fantastically influential. So I fooled around with that thing for six months or a year, and got a chance to do a couple of fill-in things on an Atlanta TV station when somebody'd be sick.

Did you have any formal training on steel?

I took one lesson, but I'd get records and sit around playing to them. That's how I really got started. This was around '49 or '50. Then when Bud Isaacs came out with a pedal guitar on "Slowly" by Webb Pierce, that shocked everybody, wondering how he got that sound. I guess I was the first one around Atlanta to get a pedal guitar: I had one pedal on a four-neck steel. It really looked funny. I made it myself, and it was huge, really too big to carry on the road or anything. I was playing in clubs all around Atlanta, then right after that I formed my first band.

What kind of group was that?

I had some pretty big stars working with me back then: Jerry Reed, Joe South, Doug Kershaw was playing fiddle, Roger Miller was playing fiddle with me, and country singer Jack Greene was playing drums. And we got fired because we weren't any good! I was on television in Atlanta for three and a half years, but we kind of wore ourselves out, so I decided to move to Nashville.

Why Nashville?

Roger Miller had come on to Nashville, and I had a brother there, Jack, who played bass with Ernest Tubb for 24 years. Jack died last year. At first Jack didn't want me to come, because the steel guitar was kind of dead then, in 1959. Everybody was trying to go pop. They was putting strings and horns on Webb Pierce records, and nobody was using steel guitar. So I starved to death the first year and a half. Then I worked with Don Gibson a while, then Marty Robbins.

When did you begin getting record session work?

I guess what really got me in was the "Pete Drake style" on the C6th tuning. When I first came up here everybody thought it was square, so I quit playing like that and started playing like everybody else. Then one night on the Opry, just for kicks, I went back to my own style for one tune behind Carl and Pearl Butler. Roy Drusky was on Decca then, and he come up to me and said, "Hey, you've come up with a new style. I'm recording tomorrow, and I want you with me." So I cut this session with him, and the word kind of got out that I had this new style (actually, it was the same thing I'd been playing for years in Atlanta, but it was new in Nashville). That month I did 24 sessions, and it's been like that ever since. That was in the middle of 1960, and that first record was "I Don't Believe You Love Me Any More," a number one record. Then I recorded "Before This Day Ends" with George Hamilton, and it, too, became number one. I just couldn't do anything wrong there for a long time.

How did your "Talking Guitar" thing come about?

Well, everybody wanted this style of mine, but I sort of got tired of it. I'd say, "Hey, let me try and come up with something new," and they'd say, "Naw, I want you to do what you did on So-and-so's record." Now, I'd been trying to make something for people who couldn't talk, who'd lost their voice. I had some neighbors who were deaf and dumb, and I thought it would be nice if they could talk. So I saw this old Kay Kayser movie, and Alvino Rey was playing the talking guitar. I thought, "Man, if he can make a guitar talk, surely I can make people talk." So I worked on it for about five years, and it was so simple that I went all around it, you know, like we usually do.

How did the talking guitar work?

You play the notes on the guitar and it goes through the amplifier. I have a driver system so that you disconnect the speakers and the sound goes through the driver into a plastic tube. You put the tube in the side of your mouth then form the words with your mouth as you play them. You don't actually say a word: The guitar is your vocal chords, and your mouth is the amplifier. It's amplified by a microphone.

When did you first use it on records?

With Roger Miller. He had a record called "Lock, Stock And Teardrops," on RCA Victor, but it didn't hit. Then I used it on Jim Reeves' "I've Enjoyed As Much Of This As I Can Stand." I really thought I'd used the gimmick up by the time Shelby Singleton and Jerry Kennedy of Mercury Records wanted to record me. I had already recorded for Starday [a Mercury label] some straight steel things like "For Pete's Sake," but I went ahead and cut a song called "Forever" on the talking thing. It came out, and for about two months didn't do a thing; then, all of a sudden, it cut loose and sold a million. So then I was known as the "Talking Steel Guitar Man," and did several albums for Smash, which is a subsidiary of Mercury.

Do you still use the Talking Guitar?

Now I'm back into producing a lot of records, and not using it much. I've been so busy recording everybody else, I haven't had time to record myself.

Tell us about your experiences getting into the pop field with the pedal steel.

You know, the steel wasn't accepted in pop music until I had cut with people like Elvis Presley and Joan Baez. But the kids, themselves, didn't accept it until I cut with Bob Dylan. After that I guess they figured steel was all right. I did the John Wesley Harding album, then Nashville Skyline and Self Portrait. Bob Dylan really helped me an awful lot. I mean, by having me play on those records he just opened the door for the pedal steel guitar, because then everybody wanted to use one. I was getting calls from all over the world. One day my secretary buzzed me and said, "George Harrison wants you on the phone." And I said, "Well, where's he from?" She said, "London." And I said,. "Well, what company's he with?" She said, "The Beatles." The name, you know, just didn't ring any bells-well, I'm just a hillbilly, you know (laughter). Anyway, I ended up going to London for a week where we did the album All Things Must Pass.

Is that how Ringo came into it?

Ringo Starr asked me to produce him, so I told him I would if he'd come to Nashville, so he did and cut a country album which was really fantastic. It was good for Nashville, and, you know, I really wanted Nashville to get credit for it. Those guys, Ringo and George Harrison, really dig country music. And they're fine people, too, just out of sight.

What kind of instrument do you play now?

Since I came to Nashville I have been playing Sho-Bud guitars and Standel amplifiers. I have some Sho-Bud amps, too. I've got four different guitars that I use with different artists. I try to change my sound around so it doesn't seem like the same musicians on each record. I was looking in the trades the other day, and found that I was on 59 of the top 75 records in "Billboard."

How about different tunings?

Yeah, I change a little. All my guitars have a little bit different pedals, enough to keep me confused. I, and just about everybody in Nashville, use basically the E9th with the chromatic strings and the C6th with a high G string. But everybody has their own pedal setups. I've got one pedal I call my Tammy Wynette pedal that I use with her; and I cut a hit with Johnny Rodriguez recently, "Pass Me By," so I got me a Johnny Rodriguez pedal, too (laughter). If something hits big I try to save that for that particular artist.

Is your equipment modified?

My amps are just stock. As for my steels, I get Shot Jackson [of Sho-Bud in Nashville] to fix them up for me. If I want to raise or lower a string, I'll go to him and say, "Can you do this?," and he'll say, "No," then go ahead and do it. We did my Tammy Wynette pedal that way: I showed him how we could make it work with open strings, so he fixed it, and it was the most beautiful sound I every heard. So the next day we cut "I Don't Wanna Play House" with Tammy, and it became a number one record.

You mentioned Jerry Byrd as a great inspiration, Whom else do you enjoy?

Well, there's so many of them now, Lordy. I look at it kind of differently: There's the recording musician and the everyday picker. They're really not the same. A guy that's really great on a show may not be any good at all on a session, or vice versa. For recording, I think Lloyd Green, Weldon Myrick, Bill West and Ben Kieth are fantastic. They know how to come up with that little extra lick that you need to make a song. Hal Rugg is also a good recording steel man. For really technical playing, Buddy Emmons is a fantastic musician. Curley Chalker is my favorite jazz steel player, but in the studio I'd have to go with the commercial thing because I'm trying to make a dollar. You know, you can play over country people's heads, and I don't think they're ready for the jazz thing. I mean I like to listen to it, but it's "musicians' music," and musicians don't buy records (laughter).

What do you think is the future of the steel guitar and country music?

Right now something is happening that I've wanted to happen for a long time: Music's coming together. It's not country music, it's not pop music, it's music. Somebody said there's only two kinds of music-good and bad. I like a little bit of it all.

Herb Remington

South Bend native pays tribute to Western Swing legend

From the South Bend Tribune

By Eric B. Hurtt

Tribune Correspondent

South Bend native Herb Remington, steel guitarist for the Western Swing band the Texas Playboys from 1946 to 1950, remembers Bob Wills, the leader of the group, as a "wise old boy" who was worthy of his legendary status in country music.

"He knew how to run a band, and he knew how to treat musicians," Remington said. "He knew how to put something together to sell records. We had to be versatile."

Wills, a Texas fiddler like his father and grandfathers, formed the Texas Playboys in 1933 in Waco, Texas, and eventually moved the band to California.

Wills and his Western Swing compatriots cast a long shadow, and this weekend the Chicago Country Music Festival pays tribute to this legend. Remington and other former members of the Texas Playboys - now called the Playboys II - are part of this tribute, performing alongside other bands such as Big Sandy and his Fly-Rite Boys and the Hot Club of Cowtown.

Remington, who graduated from Riley High School in 1944, began playing the Hawaiian steel guitar in his early teens.

"I was already playing some standard guitar, and my mother bought me lessons at the Honolulu (Conservatory of Music) on South Michigan," he said. "My teacher was Oscar Moser, who had come over from Goshen. He lives in Texas now - we're still close friends. Back then, he must have been all of 20, but to a 14-year-old, that seemed like a grown man."

While still in high school, Remington was part of the Honolulu Serenaders, a four-piece band playing "a little bit of everything." The group played weekend gigs in South Bend and Mishawaka at venues like the Green Star Cafe, the State Line Bar and Grill and the Royal Cafe. He earned $12.50 each for three nights a week. Remington's playing caught the attention of Mishawaka native Buddy Emmons, a steel guitarist who would later play with country music notables Ray Price and George Jones. Emmons' father would bring his young son to hear Remington play.

"Buddy wanted to be a prizefighter back then, but he wound up turning into one of the greatest (steel players)," Remington said.

After high school graduation, Remington headed west.

"When I went out to Los Angeles in 1944, I went out to join a Hawaiian band, but there weren't any openings," he said. "My intent was to go to Hawaii and stay there."

Remington played with various Western Swing bands before he was drafted into the Army He packed a single neck steel and a small amplifier in his barracks bag and headed for Fort Bragg in North Carolina, where he was stationed until 1946. There, he put together a group to play officers' and service clubs, adapting popular swing and hit parade material to the steel guitar.

After his military discharge, Remington returned to Los Angeles. At that time, Wills and his Texas Playboys were in high demand, and Wills had taken up the practice of forming spinoff bands to handle extra dates.

Wills was auditioning steel guitarists for a spinoff known as the Rhythm Busters, led by his younger brother, Luke. Remington auditioned for the Rhythm Busters, but Wills hired him for the Texas Playboys. Remington played that night at the Santa Monica Ballroom on Santa Monica Pier.

Remington's first gig was one of the now-legendary battles of the bands that pitted Wills against Spade Cooley's Western Swing orchestra.

"Cooley's band was on the east side, or to the right of us. We set up on the left side of the stage; it was a huge stage," Remington remembers. "That's when they had the coast-to-coast broadcast, and that was my first night. That's when I dropped my steel bar (used to fret a steel guitar) on the crowd.

"San Antonio Rose" was Bob's theme song, and we hit that first to start the show. The bar scooted out of my hand and hit the floor in front of the bandstand and rolled around all those hundreds of people, and they retrieved it, but it was too late. (Former Texas Playboy) Noel Boggs happened to be standing at his guitar with Spade's band on the opposite side of the ballroom. Of course everything was miked, and he grabbed it and took it and never missed a note. I thought `Well, this is my first and last,' but Bob said, `We'll give the kid another chance."'

The next day Remington left with the Texas Playboys on a three month tour. Wills put Remington on a weekly salary of $125. This was an incredibly busy time for the Texas Playboys, and they were on tour constantly, with radio shows and recording sessions in addition to nightly performances.

Remington left the Texas Playboys in 1950, working briefly with T Texas Tyler and Hank Penny (Remington and Penny cut the instrumental "Remington Ride") before moving to Houston with his wife, Melba.

Since 1978, Remington has been a retailer of steel guitars and builds his own line of steel and pedal steel guitars. He still plays with regularity in the Houston area and plays a few shows a month with the Playboys II.

Poco's Steel Guitarist Stretching Out

Rusty Young

by Jim Crockett

Guitar Player Magazine Nov/Dec 1972

"I'll do whatever it takes to make the pedal steel popular, to show people that it can fit into everything, that it's not just for Hawaiian music." So states Rusty Young of Poco, the man who uses Cry Baby wah, some fuzz, will bar with an aluminum kitchen chair, is experimenting with playing through a ring modulator, will triple-dub on record to lose-the traditional steel sound, is using a new bar to obtain a sitar-like feeling, will play through a Leslie for organ effects, and will turn to an electric dobro with humbuckers and a wah pedal.

Always on the lookout for new applications of the pedal steel, Rusty has used and discarded more gimmicks than most players see in a lifetime. Though he's only 26 years old, he has 19 years of steel experience and has worked professionally since he was 14. "All the gadgets," he says, "are just ways of trying to get people to see that the instrument has so many more uses than they think. We're only beginning to discover the pedal steel's real potential."

Rusty is the first to say that gimmicks aren't substitutes for technique. "You don't need all that, you don't need 15 pedals and 85 knee levers. I've seen Buddy Emmons sit down with just two pedals and'play more than guys with all the equipment in the world." Because they came from the pre-pedal era, Rusty feels, players like Emmons were deeply into technique, so that when Buddy converted to pedal steel there wasn't anything he couldn't do. "Gimmicks don't make the difference between the pro and the non-pro," Young says, "technique does."

In this respect, who does Rusty consider "pro" and who "non-pro9" He feels, "The professionals are guys like Jay Dee Maness, Ralph Mooney, Buddy, Lloyd Green, Hal Rugg, Pete Drake, people like that. The non-professionals are players like me, who can do some good things, but aren't really in the class with Buddy and the pros. Jerry Garcia is a non-professional, so is Sneaky Pete, Red Rhodes. Like, Red doesn't have the hands and feet of Emmons. He's awkward, but he still plays some nice stuff. They all do."

Rusty began with a lap steel when he was seven. "At that time," he recalls, "the teachers in Denver liked to start beginning guitarists with it, and then move them to standard guitar. This way they could sell the kids' folks two guitars." But Rusty decided to stick with steel, but with the result that when his friends were into surfing music in '64, the 16-year old was still saddled with an instrument that everyone thought was only good for country music. But country sounds came natural to Rusty since his parents loved C&W music, and used to take their young son with them when they went "honkytonkin'". "They'd sit me up on the bar, give me an orange soda and let me watch the country bands all night," he says.

Rusty played lap steel until 1960, then bought one of Denver's first pedals, a Fender 1000 doubleneck. Then, by 14, he was working the hillbilly taverns in towns like Cheyenne for $5-15 a night. "One time, I remember, during the Frontier Days I hit my peak - $20." By his senior year in high school, Rusty Young had abandoned hopes for a scientific career in favor of music, and was working six nights a week after school in clubs.

Even when he enrolled in Colorado University, his schedule remained unchanged: Classes until two, giving lessons until late evening, playing in a bar until the early morning. Fortunately for his physical and academic wellbeing, Poco came up at the end of his second year of college.

A close friend who doubled as equipment manager for both the Turtles and Buffalo Springfield had been trying to find a band that Rusty's pedal steel could fit in with. In 1968 he let the guitarist know about a Springfield record session and an audition with the International Submarine Band (later the Burrito Brothers) in California, so Rusty packed up and headed west.

He did the steel track on "Kind Woman" for Springfield's Last Time Around album, and went over so well that Jim Messina and Richie Furay, who were splitting from the band, asked Rusty to join the new country-rock group they were forming. That agreed, the trio began searching for drummers. After many months and many a disappointment, Rusty recalled a Denver friend, George Grantham. "George had been out looking for a straight job," Rusty remembers, "so when he showed up in penny loafers and short hair, Richie and Jim thought I'd lost my mind. But he played just the kind of drums we needed and could sing. He was perfect."

The steel guitar would be good for unusual sounds, but just wasn't a strong enough lead instrument. Richie only played rhythm then, and Messina was playing bass. Another Denver friend, Randy Meisner (now with Eagles) came to the rescue and played bass so Jim Messina could move to lead.

When Messina later left the band, Richie turned to lead.Six months of rehearsals came to a head when the band, now known as Poco, played a half-hour Monday night audition at Los Angeles' Troubador at the end of '68. From that came their first gig, playing there second-billed to the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band for $500 a week. Five record companies came calling as a result of the appearance. Atlantic Records had been fronting some studio time, but when Poco signed with Columbia the band had to re-pay Atlantic. "We were all so new," Rusty says, "that we didn't know when we were getting burned. We signed for 12 albums in four years, which is way too many. We had to get a lawyer so we could at least reduce it to nine."

The Fender 1000 double neck was Rusty's first pedal steel. He played it until 1964 when he made an endorsement arrangement with ZB which lasted until early in 1972 when he switched to Sho-Bud. The change from ZB shocked Rusty's fans, and probably even the ZB people. "I went to Sho-Bud," he explains, "because ZB hadn't changed or, improved. Tom Brumley was the president for a while, but he was a musician and couldn't get into the business part of it. The new owners are interested in steel, but are carpet business people, and care primarily about things like costs and such. They'd try to cut corners by using the cheapest keys and things. The strings were hard to get to when they needed changing, and here I was one of their endorsers but they wouldn't listen to me when I offered suggestions on things like that. And because I travelled, all over the world, my instrument would get beat up, but the people couldn't understand it, and they'd hassle me all the time about it."

A Denver friend, Don Edwards, runs Guitar City there, and turned Rusty on to a Sho-Bud Professional. "Don is like my mentor," the guitarist says, "and when he said he'd found a model I might like I went right in and tried it. It has Grover keys, the best pedal changer system I've played, and I can change tuning in an hour instead of having to send away for parts."

Rusty has always used Fender Twins for amps, and puts in Lansing speakers because he likes their sound with the Fender reverb. "And I prefer tubes, too, because the sound doesn't decay as fast as with transistors. I used to modify the Twins to have twice the power with Altec speakers, but that was just too strong for our sound, so I went back to new Twins, which are just as good as the old ones." Rusty's love for tubes, though he admits it's all personal preference, reaches fanatic proportions. "Tubes are very important to the sound," he claims, "as important as the speakers. We prefer RCA's, and like to find perfectly matched ones, so will try out a whole bunch until we'll find two that are as identical as possible."

In addition to the Twins, Rusty plays through a Leslie, beefed up with heavy 15" speakers, and powered by a Fender Showman top. Poco carries its own sound company on. the road to control all of this. The band prefers to play with the minimum amount of amps, going through the PA system instead. "The PA man can better balance the sound," Rusty feels, " "and a wall of amps just fight him. He can make the sound as loud as necessary, while we can hear ourselves better on stage. A mess of six-foot amps really isn't necessary. They're just for show."

National fingerpicks and a Dobro medium thumb pick are his favorites, and he uses Don Edwards Custom Strings on the Sho-Bud. This man who loves any new gadget that will enable him to play better, is most proud of another Edwards innovation, a light beam volume pedal. "I used to use a Bigsby," he says, "but this one is quieter and has a more even sound. A volume pedal has to be accurate and fast. The Edwards one works on a photo cell, so there's no pot to wear out. And if it breaks down on the road, all I have to do is go to any gas station and buy a simple light bulb." For the wah-wah effect, Rusty likes the Cry Baby, "because the bass and treble are so well balanced at the same level."

Equipment, as might be suspected, plays a major role in Rusty, Young's music. "Every piece is important, because I depend on, everything being exactly the same each night. Our equipment manager is really great this way. I know the strings are always right, the picks and bar are there and I'm the same exact number of inches from my amp."

Rusty's tuning (see "Suite Steel" article in Sept. GP) is basically standard. The C6th neck (based on chords) is his favorite and is used for the swing and semi-jazz things. It goes through the Leslie. The'E Chromatic neck (based on intervals) is mostly for country. "Using what people call a `universal' type tuning doesn't make sense to me," Rusty claims, "because any tuning that is both, loses a little of each. The C6th and the E Chromatic are each different and for different styles. A real pro can play both of them well."

For a couple of years, Rusty has been developing a pedal steel method book, but as yet no publisher has taken him up on it. "They either want to promote the name `Poco,' or want to change the book around. I think I know what a lot of the younger steel players want in a book, so I'm not about to change things because some editor who never played steel will like it."

The book was the logical outgrowth of Rusty's years of teaching, his experience, and his realization of the lack of many steel methods. He believes in his book as, much as he believes in his music, so it will eventually find the kind of publisher Rusty wants. Eventually.

"I learned to play," he says, "by copying licks over and over from every steel record I could find until I could understand the principle of solos, then I started making up my own licks. And I'd go see every steel player who came through Denver. They'd talk to me, show me things and ask me to play a little so they could give me a tip or two. It was all great learning experience, but I think any young player needs a teacher most of all: The best equipment, all the steel records he can find, and a good teacher. When I was 15-16 I idolized Ralph Mooney. He was with Buck Owens then. I memorized every one of his albums. That's a good way to start."

Rusty realizes that his dream of the pedal steel being an established instrument is a long way off. "Even in Poco, it's just a gimmick. It's there for style, it's the sweetening. Without it, everything would sound alike. In the beginning, Poco was more of a country band, but for commercial reasons we've gone more rock. But the steel is important to Poco. If it weren't, I'd leave."